A Dual-System Perspective

Decision-making

is a fundamental psychological process, central to human behavior. Over the

years, psychologists and cognitive scientists have sought to understand how

individuals make choices, weigh options, and sometimes, make mistakes. A

particularly influential framework for understanding decision-making is the dual-system

theory, often associated with the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

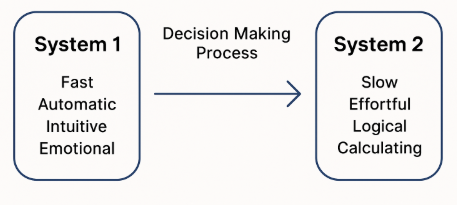

According to this model, two distinct cognitive systems govern human thought: System

1 and System 2.

System 1: The Intuitive Executor

System 1 is characterized by its speed,

automaticity, and emotional grounding. It operates without voluntary control,

drawing on intuition, experience, and emotion to produce quick judgments.

Everyday decisions—such as recognizing a familiar face, responding to a

friend's tone of voice, or driving a well-known route—are dominated by System 1

processing.

Because it

relies heavily on heuristics (mental shortcuts), System 1 enables humans

to navigate complex environments efficiently. However, this reliance can also

make us susceptible to cognitive biases such as confirmation bias,

availability bias, or stereotyping. For instance, if a person once had a

negative experience with a particular dog breed, System 1 might

automatically trigger fear whenever encountering that breed, regardless of the

individual dog's behavior.

System 1 is

indispensable for survival. Its rapid judgments were evolutionarily

advantageous, enabling early humans to react instantly to threats without the

delay of logical deliberation. Even in the modern world, System 1 helps us make

countless daily decisions without overwhelming our mental resources.

System 2: The Rational Deliberator

In contrast,

System 2 represents the slower, more deliberate, and logical mode of

thought. It activates when tasks demand concentration, reasoning, and

analysis—such as solving a complex math problem, planning a detailed project,

or critically evaluating a political argument.

System 2

thinking requires effort, and as such, it is resource-intensive.

Engaging System 2 can lead to more accurate, rational outcomes, but because it

consumes cognitive energy, humans often avoid activating it unless absolutely

necessary. Moreover, System 2 can be "lazy": it frequently accepts

the intuitive judgments of System 1 unless specifically prompted to question or

reassess them.

For example,

when someone first encounters a news article that aligns with their beliefs

(System 1’s domain), they might accept it uncritically. However, if they engage

System 2, they might scrutinize the evidence, recognize potential bias, and

form a more nuanced understanding.

System 2

also serves a monitoring function. It can override automatic responses

when they are inappropriate, such as when resisting an impulsive reaction in

favor of a measured response. However, its effectiveness depends on factors

like motivation, cognitive capacity, stress, and fatigue.

The Interaction Between Systems

While often

portrayed separately, System 1 and System 2 continuously interact.

System 1 generates impressions, feelings, and intuitions. System 2 may endorse

these intuitions or question them, leading to revision or suppression. In many

cases, we live comfortably with System 1’s outputs. Yet when faced with

unfamiliar, high-stakes, or conflicting situations, System 2 is summoned to

perform a more thorough analysis.

This dynamic

interplay explains many paradoxes in human behavior. For example, a person

might impulsively buy an expensive item (System 1) and later rationalize the

purchase with elaborate justifications (System 2), even if the initial decision

was purely emotional.

Implications for Daily Life

Understanding

the distinction between System 1 and System 2 has profound implications:

- Awareness of Bias: Recognizing when System 1 is

at work can help individuals become more mindful of biases and strive for

more reflective thinking.

- Improving Decision Quality: Knowing when to deliberately

engage System 2 can lead to better decisions, particularly in important or

complex situations.

- Stress Management: Under stress, System 2

capacity diminishes, and we revert more strongly to System 1. Managing

stress can thus help maintain rational decision-making abilities.

- Education and Training: Techniques that foster

critical thinking and metacognition can strengthen System 2 activation and

monitoring skills.

Conclusion

The

dual-system framework offers a compelling lens through which to understand

human decision-making. System 1 provides speed and efficiency but at the

risk of bias and error. System 2 offers logic and thoroughness but

demands effort and vigilance. A wise decision-maker is not one who relies

solely on one system but rather one who understands when to trust intuition and

when to slow down for thoughtful analysis. Balancing these systems is essential

for navigating the complexities of the modern world with both agility and

wisdom.

Comments

Post a Comment